Animals Aren't Food Where Do You Draw The Line?

Many people are surprised to find that insects, jellyfish and sea urchins are animals. Animals are generally thought of as medium-sized 4-legged creatures with two sets of eyes and ears — those with features like to ourselves.

While the kingdom Animalia spans from tapirs to tardigrades, the latter is absent from zoological exhibitions and beloved Graeme Base of operations picture books.

Although this omission may exist excused in children'south literature, a similar distinction appears to be made in serious scientific decisions. This is the field of creature enquiry ethics.

A research 'animal'

Zoologists tend to agree that the animal kingdom includes vertebrates (animals with a backbone) and invertebrates (those without), but the NSW Animal Inquiry Human activity defines "brute" in the post-obit way:

creature means a vertebrate creature, and includes a mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian and fish, only does not include a homo.

Humans may be excused from this definition on pragmatic grounds, as carve up acts on human ethics in research are in place.

Yet, invertebrate animals are wholly excluded. There is no other act roofing these "non-animals". As far equally scientific research is concerned, no courage means no protection.

One exception

At a national level there is one exception. The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) in Australia defines animals as:

any live non-human being vertebrate, that is, fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals, encompassing domestic animals, purpose-bred animals, livestock, wild fauna, and also cephalopods such as octopus and squid.

Cephalopods were introduced to the guidelines in 2004, merely the justification for this inclusion has not been fabricated clear.

Well-being, stress, distress and pain

So, what is the significant difference between a vertebrate (plus cephalopod) and invertebrate animal? Why the recent add-on of cephalopods? And how does a species become entitled to upstanding protection?

The Australian Code of Practise leaves some clues. They focus on iv aspects that should be considered in animal enquiry:

- well-existence

- stress

- distress

- pain.

Every bit these are all subjective states of affairs, it is hard to assess whether or not an beast experiences them. Nosotros can usually identify these things in other humans, as they act in a fashion that nosotros would when distressed ourselves – just animals adapted to unlike lifestyles may behave differently to us.

Tourists watching a captive elephant swaying may think it is being playful, when in fact the creature is distressed.

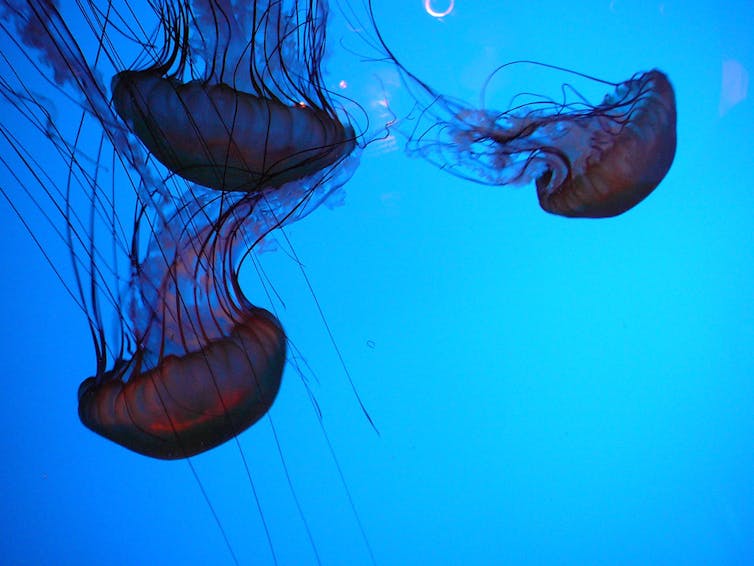

Even in closely related animals, such as chimpanzees, some behavioural displays are difficult for us to interpret. If this is the case, what promise practise we have for identifying a stressed-out jellyfish?

A physiological account

Because of these limitations, it appears that the NHMRC have resorted to a physical account of pain and distress. Co-ordinate to the code:

All vertebrates possess the anatomical and neurophysiological components for the reception, manual, central processing and retentivity of painful stimuli. Some of these features are besides nowadays in some college-order invertebrates, such as octopus and squid. This, together with analyses of animal behaviour, supports the view that an brute may have subjective experiences of pain like to those of humans.

This indicates that the 2004 cephalopod revision was done in calorie-free of research concerning the complexity of their nervous system. Merely it is possible for in that location to be other invertebrate animals with components for the reception, manual, processing, and retentivity of hurting. The lawmaking does not deny this possibility, but it also does not acknowledge it.

In the same mode that some animals have unlike behavioural responses to pain, it is possible that invertebrates have different underlying physiologies related to pain transmission, reception and memory.

Not only has there non been enough research conducted on the matter, but due to the private nature of pain and well-being, it may in principle be incommunicable to carry.

Where to draw the line

Then where to draw the line on beast research? Should every beast, down to the tiniest insect, exist carefully considered before used in a scientific style? This question boils downwardly to how humans differentially value different species.

Well-nigh of us don't glimmer an eyelid when insects fly in to our windscreens on the route, but shudder at the thought of hitting a possum or wallaby. Would this kind of reasoning modify if we were to discover better evidence of pain and distress in invertebrates?

To decide what animals to include in ethical decision making, we need to get to the bottom of these kinds of intuitions and decide whether they are justified.

Although the NHMRC believe that justification lies with differences in the experience of hurting and distress, others identify value on animals for different reasons such every bit intelligence, consciousness and cocky-consciousness.

Information technology may be these reasons that permit unregulated invertebrate employ in scientific research to go along without public protest. It may as well be why the consideration that these creatures could endure pain and discomfort — despite differing underlying physiologies — remains inhibited.

A friend who taught ethics classes at primary schoolhouse final year asked children why some animals should be protected over others. One of the resounding responses was "because they are cute".

While this may seem childish and charming at face value, recall about the way some people beat at harmless spiders with a shoe: would they behave the aforementioned way if they did not have their "creepy crawly" advent?

Source: https://theconversation.com/when-is-an-animal-not-an-animal-research-ethics-draws-the-line-21756

Posted by: falconefifue1964.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Animals Aren't Food Where Do You Draw The Line?"

Post a Comment